Communities

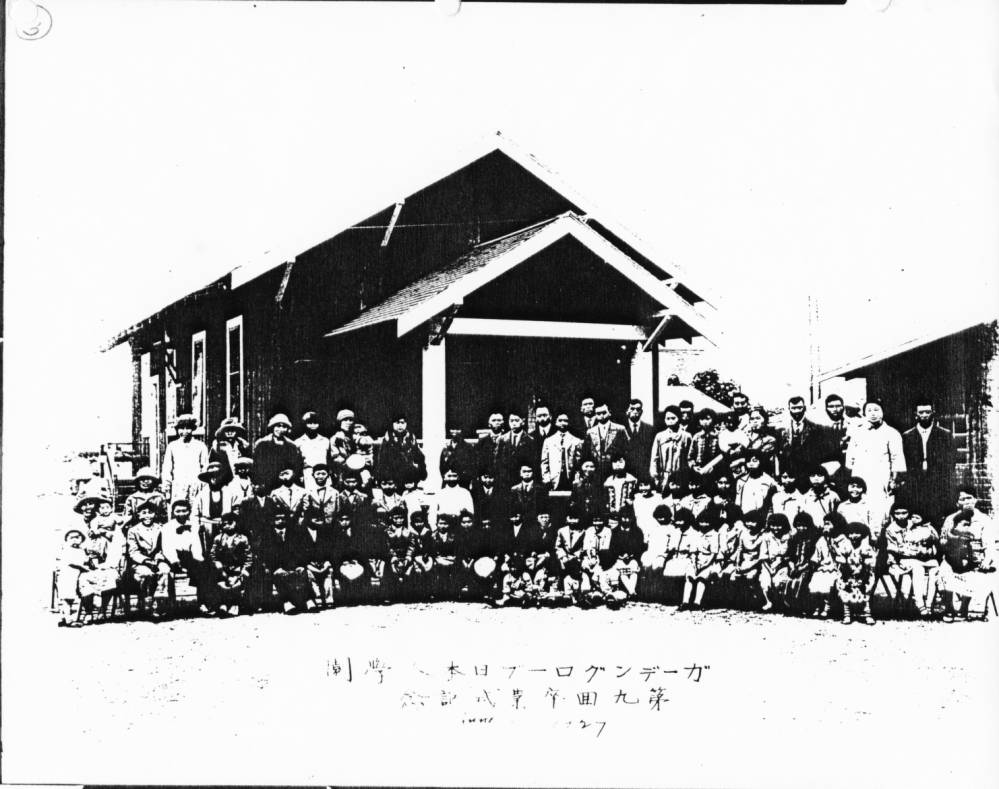

In Orange County, Japanese people came together for many reasons. Closeness and work are the most obvious ones—farmers living near each other were more likely to know and associate with one another. Those living in Wintersburg generally had less to do with those in Anaheim or La Habra. And, quite a few Japanese who settled in Orange County were from just a couple prefectures. While organized kenjinkai (prefectural associations) did not seem to be a large factor in most people’s lives, they did serve as tethers to attract others from the same prefecture or even county. Schools were also important community spaces for Orange County Japanese, which makes up the main map here.

In this section, we will talk about different types of communities that existed in Orange County. One is the “lost” community that existed in Irvine up until World War Two. Apparently, the Irvine Ranch lands were home to a few close-knit communities, often organized by prefecture. But that community seems to have vanished after World War Two.

A second community is the religious community. For some, religion was a key factor for why they came to the U.S., and animated much of their lives in and out of Orange County. Christianity was a focus of many Japanese in Orange County, and for others Buddhism was natural, if a bit mundane.

A third community were the generational communities. Different generations behaved and associated in wildly different ways. Issei, Nisei, and Kibei all tended to have different ideas about the way things ought to be, and when we talk about incarceration, those differences are very obvious.

The fourth “community” is Clarence Iwao Nishizu. His narration was so rich, interesting, and riddled with connections to the religious, prefectural, and business communities, that it deserved its own section.

"Lost" Communities

Today, Irvine, CA in central Orange County is a fairly multicultural planned suburban city. This transformation into suburbia (and a city) only began in the 1960s and 1970s, and accelerated over the years. Before that, the Irvine Ranch, made from the land that would be Irvine and small parts of Newport Beach, Newport Coast, Tustin, and Santa Ana, was privately owned farmland. From these oral histories, we know that Japanese lived and worked on the Irvine Ranch during the prewar, but their communities seem to have not been very durable.

Of these narrators, only Shizu Kamei, Yoshiki Yoshida, Takeo Yamada, and Kenji Kikuchi lived on or interacted with the Irvine Ranch lands. Shizu Kamei lived on the Irvine Ranch from 1933 to 1935, farming tomatoes, squash, and celery unsuccessfully near what is known as Peter’s Canyon. They left to Santa Ana in 1935. Yoshiki Yoshida moved to the Irvine Ranch in 1919, just before many Japanese would leave the Irvine Ranch in 1921, because of the Alien Land Laws. Presumably, because the Irvine Ranch was managed by the Irvine Company, they were unwilling to face the potential legal risk of skirting discriminatory laws, where friends or enterprising individuals might have been. Even so, Yoshida returned to the Irvine Ranch from Chula Vista in 1933. While in Irvine, Yoshida went to Tustin High, Santa Ana Junior College, informally took over his father’s Irvine farm, and began participating in a Kendo class in Laguna Beach—probably referring to what is known as Crystal Cove today. Takeo Yamada farmed on Irvine Ranch land in 1940 for a short period of time. And, according to Clarence Nishizu, Kenji Kikuchi, the Wintersburg Church pastor, founded the Crystal Cove Japanese Language School in 1929.

According to at least two narrators, the Irvine Ranch land contained many Japanese families and small communities, whether they existed along the Pacific Coast Highway or near the foothills of the Santiago Mountain Range. But, today, aside from the Crystal Cove State Park and Crystal Cove Conservancy’s efforts, there seems to be little trace of there ever being significant Japanese farming enclaves around Irvine. According to Nishizu, the Crystal Cove area became a popular place for Japanese farmers because a Mr. Sakamoto and Mr. Yamashita introduced many other Japanese families to the area in 1929. Students around this community attended Newport Grammar School until Japanese children were refused attendance by the Newport Harbor School Board. The Laguna Beach Growers Association was also formed as a kind of seed-buying cooperative. But there were other enclaves. Yoshiki Yoshida says that his family farmed tomatoes on the hillsides north of Irvine Boulevard (today Irvine Boulevard is a fairly central main road that runs parallel to the 5 Freeway through residential and commercial areas). Yoshida even described that Irvine had “six villages” of Japanese people living together on Irvine Ranch Land. In other words, there were a significant number of Japanese people living on the Irvine Ranch, enough to merit community institutions like growers’ associations and language schools.

But perhaps two clues help us understand why the Japanese communities on the Irvine Ranch dissolved so easily as prejudice heightened and Japanese were incarcerated. As mentioned above, around 1921, many Japanese left the Irvine Ranch because of the Alien Land Law. The unique position of the Irvine Company as a major landholder and agricultural business probably made it fearful of the legal ramifications of allowing many Japanese to lease its land. However, Yoshida was clear that “most” of the Japanese moved from the Irvine Ranch, not all. His uncle was one that never left the Irvine Ranch: “He went to work for the Irvine Company, and when it got to a point where they could go back to farming again—Irvine was going to accept this dummy company to run the deal—then he went back to farming again.”1 Yoshida returned to Irvine Ranch land in the early 1930s—Nishizu also described many Japanese moving to or returning to the Irvine Ranch in the early 1930s. Moreover, Takeo Yamada, who spent only a short couple years in Irvine, described his family as moving land every couple of years because the soil would suffer from disease. So, probably both the climate of legal discrimination and some recurring patterns of movement contributed to a weakening community.

But how could a community be so weakened that there is little to no mention of it enduring after incarceration? Did the Irvine Company’s policies and practice play a role? The six villages that Yoshida described formed in part because of the Irvine Company’s policies. He says that:

“[the] Irvine Company refused to let them put the house on the land, so they formed little villages where you can have the house, and you had to be in one of those places; then you commuted to the fields....That's why we had little villages, not because they wanted to have a little community by themselves, but because of the company rule that you couldn't put the house on the land that you were leasing. That's why we lived in little communities." 2

After incarceration, Yoshida believed that no one had returned to the Irvine Ranch. In his telling, they simply “didn’t have the money to go back to farming.”3 The narrators that seem to have been most successful after the war were those that could hold onto their land, especially since its value increased many times over as postwar development boomed—and the Irvine Company owned all of the Ranch land. Despite Yoshida’s somewhat negative appraisal of the Irvine Company, Takeo Yamada had a more positive outlook. After Pearl Harbor, Yamada explained that some around the Irvine Ranch lands feared Japanese dusting tomatoes was actually a smoke signal. With this tense atmosphere, Yamada said the Irvine Company was “nice enough not to let anybody come into the canyon [where they were living]—people were coming in with shotguns. The Company had a security guard.”4 In fact, after the war, Yamada said that Hugh Plum, the person in charge of leases on Irvine Company land, offered any Japanese farmer the opportunity to return to the land. Still, Yamada says that only a handful of farmers returned to the Irvine Ranch after the war.

Today, a small trace of what existed on the Irvine Ranch lands remains in the historic Cottage 34 preserved on Crystal Cove State Beach. There is also a movement to acknowledge Japanese farmers around the western U.S. while raising awareness and financial support for victims of the 3.11 disaster, pushed in large part by Irvine-based Tanaka Farms and the OCO Club. It seems that the Irvine Company’s ownership of this large swath of land in central Orange County was probably the most important determining factor to how Japanese communities formed, existed, and dissolved in the first half of the 20th century.

Citations

1. Yoshiki Yoshida, Interview With Yoshiki Yoshida for the Japanese American Oral History Project, interview by Alice Maxwell, trans. Yukiko Sato, November 19, 1983, 12. 2. Yoshiki Yoshida, Interview With Yoshiki Yoshida for the Japanese American Oral History Project, interview by Alice Maxwell, trans. Yukiko Sato, November 19, 1983, 11. 3. Yoshiki Yoshida, Interview With Yoshiki Yoshida for the Japanese American Oral History Project, interview by Alice Maxwell, trans. Yukiko Sato, November 19, 1983, 13. 4. Takeo Yamada, Interview With Takeo Yamada for the Japanese American Oral History Project, interview by Pat Morgan, March 26, 1973, 5Religion in Orange County

For Christian Japanese, religion was an important part of their lives and communities. For those that acknowledged Buddhist practices, religion seemed to be a minimal part of their lives.

Perhaps a key issue limiting the influence of Buddhism in Orange County peoples’ lives was the simple lack of a temple or organized community. The nearest temple was in Los Angeles, and besides a few of the Japanese language schools that functioned as community gathering places, there was nowhere for Buddhist devotion. Both of Yoneko Dobashi Iwatsuru’s parents were originally Buddhists and would travel to Los Angeles. However, as Iwatsuru described it, the children eventually joined local churches, “because it was too far to go into Los Angeles,” almost as if they were interchangeable. A few years after Shizu Kamei came to the U.S. and was living in Gardena, she married. For her marriage ceremony, a priest from the Nishi Hongan-ji branch in Little Tokyo came to officiate the wedding.

On the other hand, the Wintersburg Presbyterian Church in what is now Huntington Beach area, tied many people together through baptism, church attendance, and Japanese language school. Kenji Kikuchi, one narrator who became a pastor at the Wintersburg mission—and eventually church—was a part of the Orange County Japanese Christian community for many years. Several other Japanese Christians had laid the path for Kikuchi, including Reverends Nakamura and Terazawa who operated the mission in its early years. By 1928, two years after Kikuchi had arrived in Wintersburg, it was officially organized into a church. Kikuchi remarked that, in order to get children to Sunday school, he drove around the Talbert area in a Model T Ford with “about nineteen children in an open car.”1 Still, even with Wintersburg being a hub for Japanese Christians, and with a sizable community in the Talbert and Wintersburg area, other churches existed in Orange County. Charles Ishii explained that a Japanese Free Methodist Church began in Anaheim in the late 1920s, and that there was a Baptist Church in Garden Grove. Moreover, a couple interviewees remarked that they attended churches with almost entirely white congregations. Ishii even supposed that there might have been a Japanese section at a cemetery on Magnolia in Garden Grove, suggesting that Japanese were welcomed in some Christian circles even in death. For Nisei, mingling with non-Japanese at churches was much easier, because the language barrier did not play as much of a role.

For a few narrators, Christianity seemed to have a large influence on their lives. Amy Uno Ishii’s parents were raised as Christians at American missionary schools, and had no intention of returning to Japan. Like Ishii’s parents, Kenji Kikuchi was shaped by a Christian upbringing. A church minister in his community encouraged him to go to a Sendai Christian school, and for high school, Kikuchi attended Tohoku Gakuin, a school founded by Christian missionaries at that time. Throughout Kiyoshi Shigekawa’s interview, he relied on many metaphors of Christian theology to describe his life. Clarence Iwao Nishizu, likewise spent a great deal of time impressing upon his interviewer his wide knowledge of Christian theology and allegory as he described his business dealings and fortune.

For the Japanese that settled in Orange County, religion was sometimes a major ordering factor of their lives. Whether their Christianity led them to baptism and association with a church community or spiritual influence, they were some of the first Japanese Christians in Orange County. For those that adhered to Buddhist practices, Buddhism seemed to only crop up at major events in their life or as something that their parents participated in. Still, many of the narrators seemed anxious to emphasize their Americanness and may have been fairly hesitant to speak in great detail about how Buddhism influenced their lives. That tug of war between Americanness and Japaneseness is a big issue when we talk about incarceration.

Citations

1. Kenji Kikuchi, Interview with Kenji Kikuchi for the Japanese American Oral History Project, interview by Arthur A. Hansen, August 26, 1981, 3Issei, Nisei, and Kibei

Those who told their stories can roughly be divided into three generational categories: Issei, Nisei, and Kibei. Issei means first generation immigrants, and for this project, they were mostly those who arrived in the U.S. before or around the mid to late 1920s. Perhaps there were other first-generation Japanese that arrived in the U.S. after that period, but probably because of the increasingly discriminatory laws and climate, they were less likely to. Nisei were second-generation Japanese-Americans, who were the children of the Issei that decided to stay in the U.S. Many Nisei were born in the mid-1910s through the 1930s. Of those Nisei, some can be called Kibei which literally means “coming to America.” The Kibei were those that were born in the U.S., but relocated to Japan for the bulk of their schooling before returning to the U.S. Many political and cultural differences run between these groups.

Language became a major point of difference between generations. The language struggles and barriers of Issei were significant enough that those who were bilingual functioned as important bridges between communities or in legal matters. Amy Uno Ishii explained that her father was made a foreman when working on railway gangs because of his English. In other cases, Maki Kanno described that the pastors at Wintersburg Church were important liaisons when there were translation or legal issues. Of our small group of narrators, those who were long-time Christians were frequently schooled in Christian schools while in Japan, presumably exposing them to English long before migration to the U.S. Thus, those with strong Christian backgrounds were probably more likely be translators or go-betweens. On the other hand, the Nisei grew up mostly with the Japanese that their parents spoke at home. Japanese language schools popped up around Orange County, with at least seven different language schools existing in 1942 at the time of incarceration, according to Clarence Iwao Nishizu. Pastors and conscientious parents typically founded these language schools, which could function as community meeting centers, like Cottage 34 in the Crystal Cove area. However, a couple Nisei mentioned that their interest in Japanese language school waned as they got older and they eventually stopped attending.

To help communication between the first and second-generation Japanese, a group of Japanese got together to publish an Orange County-centered single-issue magazine called Echo / Hibiki. The magazine, published by the Orange County YMCA, was bilingual, and according to Nishizu, was designed to help Issei and Nisei understand each other better. In an article from Echo / Hibiki that Nishizu quoted at length, the staff editor of the Rafu Shimpo, a Los Angeles-based Japanese newspaper, encouraged Nisei to not be discouraged by discrimination, but push on. Shiro Fujioka, incorporating a tinge of myth-making about Japaneseness, wrote:

"It is a matter of regret that Americans are inclined to harbor racial prejudice toward the Japanese. This unjust discrimination will cast a shadow upon the minds of the young, second generation—but act righteously with justice true to the noble American tradition. Be just and fear not. Don't be discouraged by the depression that prevails. Don't mind the difficulty of securing employment--you must have the spirit of Bushido, and lofty ideals to cope with the evils in life.”1

The Japanese American Citizens League of Orange County was also a fulcrum for Issei and Nisei. While it was a general community organization, Roy Taketa, whose parents came to the U.S. in the late 1910s from Fukuoka and settled around Long Beach and Los Angeles, described the JACL as mostly being for Nisei. (There was also a Los Angeles chapter.) Yoshiki Yoshida, a Nisei in Irvine, was president of the OC JACL when Japanese were beginning to be rounded up and incarcerated. He left this position to spend more time helping those who were without the male head of the family, because the FBI swiftly detained many Japanese men after Pearl Harbor. James Kanno, a Nisei who was active in incorporating Fountain Valley as a city many years later, served as president of the JACL, presumably in the postwar, and was board member in 1971 when he was interviewed. Before and during the war, Mitsuo Nitta says that the JACL was instrumental in supporting Japanese as they fought inequality, discrimination, and particularly escheat cases—legal maneuvers where the U.S. government attempted to seize land from Japanese and Japanese Americans.

Citations

1. Clarence Iwao Nishizu, Interview with Clarence Iwao Nishizu for the Japanese American Oral History Project, interview by Arthur A. Hansen, June 14, 1982, 139.Kasuya County, Business, and God: Clarence Iwao Nishizu

Of all of the interviews I read, Clarence Iwao Nishizu’s was the most exceptional for its depth, quality, and uniqueness. The interview that I read was initially conducted in 1982, but it eventually grew to be a book-length account of Nishizu’s life and the communities that surrounded him, particularly in Orange County. The reason it grew was because of the methodology that Dr. Hansen, the professor in charge of the project, used in preparing the final transcripts. They were returned to narrators for review and editing if they pleased. The result was that Nishizu continuously added, conducted his own research, and revised the transcript so that it was at last completed in 1991. Thanks to Nishizu’s enthusiasm and research for his own narrative, this present project has become richer and more expansive. From Nishizu’s narration, I derived the above map of the Orange County Japanese Language Schools, which were important community pillars for Japanese. Actually, this project probably could have derived multiple visualizations of how Japanese in Orange County related to one another based on his accounts—from family trees to business contracts.

Nishizu is one of the most interesting characters of all these narrators. Nishizu’s family came from Kasuya county, Fukuoka Prefecture on the southern island of Kyushu. In Nishizu’s telling, so many found their way to Orange County from the Nishizu’s home district there there was a “Kasuyagunjinkai””—a Kasuya County Association—in Orange County. Nishizu says that many of the seasonal workers that came through his family’s farm in the 1920s were from Kasuya county as well. Moreover, Nishizu tells of other Kasuya families in the U.S. functioning like tethers for those migrating from Japan, or those already around California. The connections of nuclear families, relatives, and neighborhood friendships in Japan endured and invigorated new arrangements in the U.S.

Nishizu also demonstrated throughout the interview that he was a devout Christian and an ambitious businessman—two things that went hand in hand for him. He began attending the non-Japanese Garden Grove Baptist Church around the 1920s. From then, Nishizu’s Christianity played a significant role in his life. He frequently described much of his luck and the circumstances that led to his success as having to do with God’s will. Sometimes that luck luck hurt his prospects in the short term. As Nishizu explained in one circumstance, he was forced to allow a highway through his land, saying that “God had a purpose in hurting me by chopping up my land.”1 After the war, Nishizu slowly found success through a farming partnership with cousins and ultimately real estate deals that made him even more wealthy. While Nishizu described the terms of loans with Japanese banks in Los Angeles many times throughout his interview, his religious zeal also accompanied his success. Nishizu described a time in the 1950s where he and his partners were in a difficult spot financing their farm, so he turned to a banker, who he knew to be a devout Christian. In Nishizu’s telling, simply mentioning the “story of talents in Matthew 25:14” served to secure he and his partners their loan.2 Nishizu’s faith endowed him with confidence and hope throughout his business dealings as he secured more land, mobile home parks, and eventually the Rainbow Hotel in Las Vegas.

The most curious aspect that Nishizu described about his life was a Judo tour through Japan and its empire in 1931, where he met a slew of high-ranking government officials. You can see the full scope of the tour in the map above. The tour, known as the Judo Educational Tour Group (Judo Kengaku Dan), was sponsored by the Southern California Kodokan Judo Society (Nanka Kodokan Judo Yudan Shakai). Sport tours were no rarity at the time—university, semi-pro, and professional baseball teams toured between Japan and the U.S. dozens of times in the prewar period, and the tours of Black League all-stars in the 1920s and 1930s are the subject of Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan. Nishizu’s tour stands out. Nishizu, along with 11 other Nisei, left the U.S. in September 1931, stopping in Hawaii and then arriving in Yokohama. Their tour took them to many major cities down the main Japanese islands, ending in Kagoshima. But, while in Tokyo, Nishizu met Hatoyama Ichiro, Minister of Education, Isamu Takeshita, a former admiral, Fujinoma Shohei, Tokyo Police Chief, Tokonami Takejiro, Minister of Railroad, Noma Seiji, the founder and publisher of Kodansha, and General Araki Sadao, convicted war criminal of World War Two. It is not clear how or why so many high-ranking officials would meet with this rag tag Judo tour of Japanese from the U.S., but Nishizu says that the fact that their tour leader, a Mr. Yamauchi, was born in Kagoshima prefecture, allowed for them to meet with these officials. However, only Isamu and Tokonami were Kagoshima natives, so perhaps there is more to be known. After traveling through the main Japanese islands, their tour continued to Korea, visiting Busan and Seoul, before entering Manchuria’s Mukden, Harbin, and Dairen. Unfortunately, Nishizu did not describe much of his reflections on the tour. What did an American Nisei, who experienced discrimination at home, think of Japan’s subjugation of other people across its empire?